Peter Stevens Hamilton, Scribbler

- pshorner6

- Mar 5, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Apr 1, 2025

Nova Scotia # 3 on embossed July 18th, 1866, cover from Pictou, Nova Scotia to Halifax. Addressed to P.S. Hamilton, Esq., Halifax. Embossed "James Primrose & Sons, Pictou, Nova Scotia. Backstamps Pictou, N.S., JY 18 1856, H(alifax), N.S. JY 21, 1856. Red wax "Primrose & Sons" seal.

Nova Scotia # 2 on November 19th, 1858, cover from Pictou, Nova Scotia to Halifax. Addressed to P.S.Hamilton Esq., Halifax. Backstamps Pictou, N.S. NO 19 1858, H(alifax), N.S. NO 20 1858. Red "Primrose & Sons" wax seal.

Great Britain # 14, lilac six pence on 4 Sep 1860 cover from London, England to Halifax, Nova Scotia. Addressed to Mr Peter Stevens Hamilton, Halifax, Nuova Scotia. Cancallation London SP 4 60. Backstamp Halifax SP 19 1860. Red wax seal of Legazione Sardegna in Londra

Nova Scotia # 10 on 25 Feb 1861 cover from New Glasgow, Nova Scotia to Halifax, Nova Scotia. Addressed to P.S. Hamilton, Halifax. Backstamps New Glasgow, FE 25 1861, Halifax FE 25 1861

Nova Scotia # 10 on October 12th, 1861 cover from Truro, Nova Scotia to Halifax. Addressed to P. S. Hamilton, Esq., Barrister law, Halifax. Backstamps from Truro, OC 12 1861, and H(alifax), OC 12 1861.

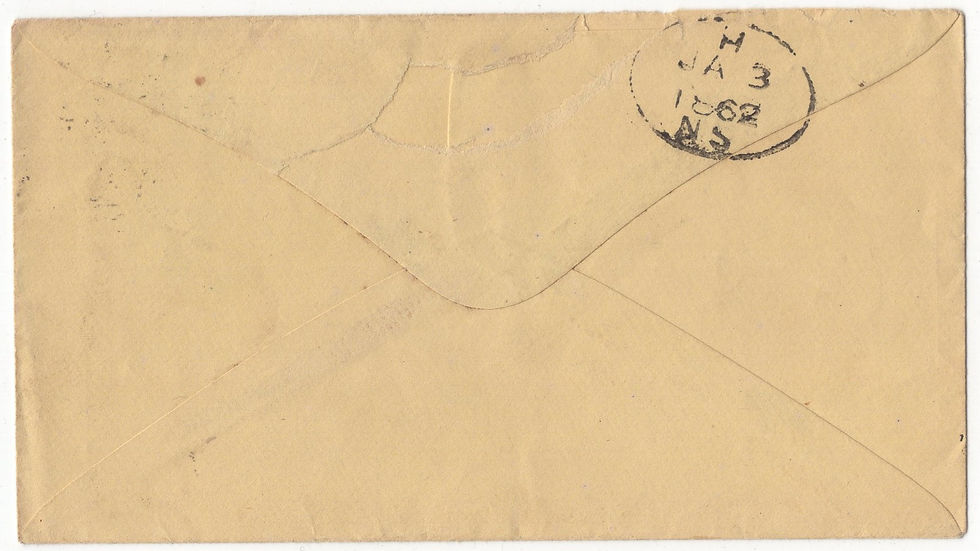

Nova Scotia # 10 on January 3rd, 1862 Halifax cover. Addressed to P. S. Hamilton, Esq., Granville Street third door south of Prince Street, Halifax, N.S. The 2c county rate didn't take effect until May 11th, 1863.

Nova Scotia # 10 on 22 Sep 1862 embossed cover from Halifax, Nova Scotia to Sherbrooke, St. Marys, Nova Scotia. Addressed to P.S. Hamilton, Sherbrooke, St Marys. Embossed Cogswell Forsyth Druggists, No. 7 Granville Street, Halifax, N.S. Backstamps Halifax SP 22 1862, Sherbrooke St Marys SP 24 1862.

Nova Scotia # 3 on embossed July 18th, 1866 cover from Pictou, Nova Scotia to Halifax. Addressed to P.S. Hamilton, Esq., Halifax. Embossed "James Primrose & Son, Pictou, Nova Scotia. Backstamps Pictou, N.S., JY 18 1856H(alifax), N.S. JY 21, 1856. Red wax "Primrose seal

Peter (Pierce) Stevens Hamilton (he published a book of poetry under the name Pierce Stevens Hamilton), lawyer, journalist, author, and Nova Scotia office holder was born 3 January 3rd, 1826, in Brookfield, near Truro, Nova Scotia, eldest son of Robert Hamilton and Sophia Stevens. He married Annie Brown on December 8th, 1849, in New York City, and they had four sons and two daughters. He died February 22nd, 1893, in Halifax and is buried in Camp Hill Cemetery, Halifax.

Peter Stevens Hamilton was a descendant of an Ulster Scots family that had settled in Nova Scotia in the 18th century. He was educated at Horton Academy in Wolfville, and Acadia College. He was forced to withdraw from Acadia because of ill health and lack of money, and studied law with Ebenezer F. Munro in Truro, where he later articled with Adams George Archibald. In 1852 he was admitted to the bar of Nova Scotia and established a law practice in Halifax. The following year he became secretary-treasurer of the Nova Scotia Electric Telegraph Company and local agent for the New York Associated Press. It was Hamilton’s responsibility to decode and transmit news dispatches from Europe as they were received in Halifax. To outwit competitors, he devised a system whereby the dispatches were placed in a sealed canister and thrown overboard as soon as the steamer entered the harbour. Upon retrieval by an assistant, they were rushed to Hamilton’s office and were being telegraphed to New York by the time the steamer docked.

An avid reader and self-styled “scribbler from boyhood,” Hamilton was happiest when writing, and consequently it was in the field of journalism that he made his mark. As early as 1846 he had been contributing articles to the Halifax Morning Post & Parliamentary Reporter and within a year of being called to the bar had forsaken an unprofitable law practice for the editorship of the Acadian Recorder. He held this position until 1861 and would continue to write for the paper on an irregular basis until 1874. Under Hamilton’s direction the Acadian Recorder adopted a crusading style of journalism, supporting a wide variety of causes ranging from better educational facilities to the need for new industry in Nova Scotia. But the most important issue was Hamilton’s all-consuming campaign for confederation with the other British North American colonies. Although the idea was far from new, he was one of the first Nova Scotians to take an unequivocal stand in support of the concept. His reasoned editorials in the Recorder, continuous pamphleteering, and extensive correspondence contributed to the marshalling of the pro-confederation forces in the colony.

Early in 1855 in Halifax he published "Observations upon a union of the colonies of British North America." This pamphlet, widely circulated at home and abroad, was also reprinted in the Quebec Gazette and the Anglo-American Magazine of Toronto. Hamilton summarized the conventional arguments for union, emphasizing that several disunited colonies would “inevitably” be swallowed up by the United States. He favoured a legislative rather than a federal union and went on to provide an interesting forecast of federal provincial conflict. “What is to be the prerogative of that federal Government; and upon what objects is that Parliament to legislate? Of what powers can the several Provincial Legislatures divest themselves to bestow upon the Federal Legislature? . . . It is clear that, in this matter of the management of the internal affairs of each Province, there could be no division of authority amicably and satisfactorily agreed upon, in the first place; and if agreed upon at all, it could only lead to clashing of rival claims with no prospect of a generally beneficial result.”

During the spring and summer of 1858 Hamilton spent three months travelling in the northeastern United States and in Upper and Lower Canada. A series of lengthy articles about the journey entitled “Notes of a flying visit among our neighbours” appeared in the Acadian Recorder between July and October. The trip provided him with an opportunity to interview leading political figures, among them John A. Macdonald, John Rose*, Christopher Dunkin*, and Thomas D’Arcy McGee*. Thus Hamilton was enabled to gauge at first hand Canadian support for confederation. He returned to Halifax with a renewed resolve to promote the union and maintained his Canadian contacts through correspondence. It was McGee who urged him to use the visit of the Prince of Wales in 1860 to publicize the concept of confederation. In the resulting pamphlet, directed to the colonial secretary, the Duke of Newcastle, who accompanied the prince, Hamilton repeated the economic and political arguments in favour of union and suggested that the duke should seek, “so far as leisure and convenience will permit,” the opinions of British North Americans on the subject.

Inevitably any prominent Nova Scotian with views on confederation would come into contact with Charles Tupper and Joseph Howe, the two leading figures in the debate. Hamilton and Tupper had been contemporaries at Horton Academy and although both supported the Conservative party, they were suspicious of each other. Throughout much of his career, Hamilton was in financial difficulty, and his continuing search for a political sinecure must have annoyed Tupper. Hamilton’s brief tenure as registrar of deeds for Halifax County in 1859 ended abruptly with the defeat of the Conservative administration of James William Johnston* early the following year. With the return of the Conservatives to power in 1863, he served first as gold commissioner and later in the expanded office of commissioner of mines. He openly lobbied for the post of secretary to the Charlottetown conference in 1864 only to be rebuffed by Tupper, who had become premier that May. Between 1864 and 1867 his relationship with Tupper gradually worsened. The final rift took place in April 1867 when the two men jostled over the nomination for Halifax in the upcoming federal election, an incident that became known as the “Good Friday game.” On 1 May Tupper had the last word when he fired Hamilton as commissioner of mines just two months before the expiration of his term.

In the early 1860s the two men had been on reasonably amicable terms and Tupper had solicited material from Hamilton for his speeches in favour of confederation. However, by 1866 relations between them had become so strained that when Tupper asked Hamilton if he would publicly rebut Joseph Howe’s anti-confederation views, Hamilton was suspicious. As he would later confide in his memoirs, “I strongly suspected that Tupper meditated some mischief toward me. Had I not known him as a boy at school, I might not have thought of such a thing.” Nevertheless, his pamphlet, British American union: a review of Hon. Joseph Howe’s essay, entitled “Confederation considered in relation to the interests of the empire” (Halifax, 1866), was one of his best journalistic efforts. By frequent reference to Howe’s many early speeches in favour of an intercolonial union and by ridiculing his “Jack-o-lanthorn imagination,” Hamilton demolished Howe’s arguments, alleging that his object in writing the pamphlet had been to “deceive the statesmen of England” and “mislead the population of Novascotia.” Ironically both men were to change sides after 1867; Howe joined the Conservatives and Hamilton drifted toward the Liberal party, serving briefly in 1875–76 as inspector of fisheries for Nova Scotia under the federal administration of Alexander Mackenzie.

In later life Hamilton resumed his journalistic career, but with mixed success. As a reporter for the Acadian Recorder in Ottawa in the early 1870s, he became a member of the parliamentary press gallery and was named vice-president of the Canadian Press Association. From time to time he dabbled in poetry; a collection of his work, The feast of Saint Anne and other poems, which appeared under the name Pierce Stevens Hamilton, was published in Halifax in 1878; a second edition was issued in Montreal in 1890. An unpublished history of Cumberland County, for which Hamilton received the Akins Historical Prize in 1880, dates from this period in his career. He apparently spent some time in the Canadian west and witnessed the arrival of the first Canadian Pacific Railway train at Port Moody, B.C., in 1886.

In 1899, six years after Hamilton’s death, a

group of friends erected a monument to his memory in Camp Hill Cemetery, Halifax. Speaking at the unveiling ceremony, Attorney General James Wilberforce Longley declared, “However much men may have differed from some of his utterances on public questions all would admit that he was a man of ability, a clever writer and thoroughly honest and patriotic in the stand he took on public questions.” The Morning Chronicle, in its report of the event, commented, “Those who profited by his labors as an advocate of union gave him the cold shoulder of neglect and left him to shift as best he could. It is not to be wondered at that he felt the bitterness of political injustice and ingratitude.” William B . Hamilton, “HAMILTON, PETER STEVENS (Pierce Stevens Hamilton),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003

Primrose & Sons

James Primrose was born in 1803 in Scotland. He was a merchant. He moved to Pictou, Nova Scotia, where he was an agent of the Bank of Nova Scotia. He founded a firm Primrose Sons, involved in insurance, banking, lumber, shipbuilding, coal mines, and the Marine Railroad Company. His sons Clarence Primrose (1830-1902) and Howard Primrose (1833-1906) became the other senior partners. After his retirement in 1864, the firm became Primrose Brothers. The same year William Norman Rudolph (1835-1886) made the transition from the clerk of the firm to merchant partner, and they became known as Primrose & Rudolph.

Comments