William Coleman, Hats, Caps, & Furs

- pshorner6

- Mar 8, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Mar 15, 2025

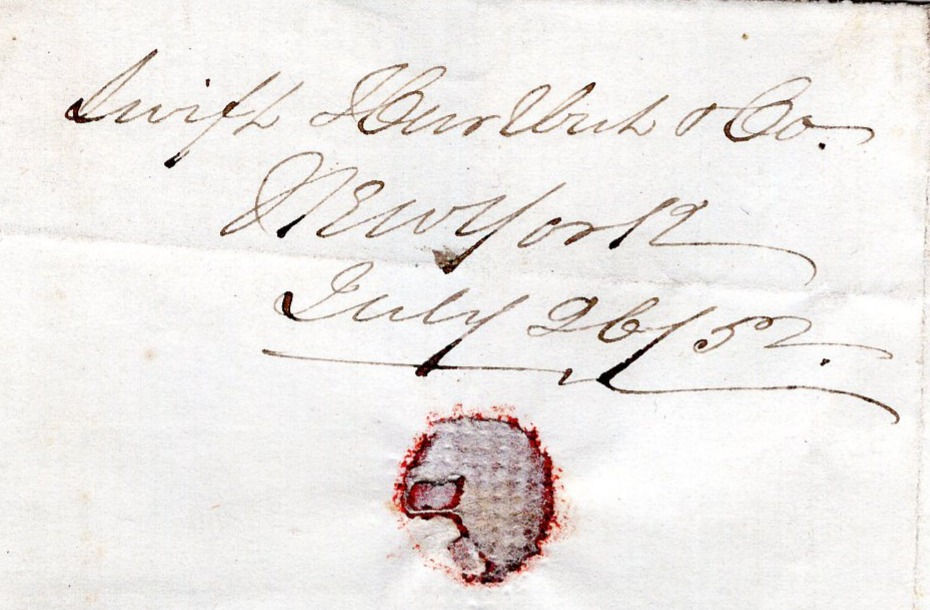

United States # 5 1851,1c Franklin blue, Type I, and 3, United States # 11 3c Washington, dull red, on 26 July 1852 cover from New York to Halifax, Nova Scotia. Addressed to Mess. W. J. Coleman & Co. Halifax, Nova Scotia. Manuscript “per steamer” on front. Cancelled NEW YORK JUL 26. Handstamp "5" on front. Backstamp, U. States, Halifax, AU 6 1852. Manuscript “Swift Hurlburt & Co. New York, July 26, 52” inside flap.

William James Coleman was 38 years old and the proprietor of W. J. Coleman & Sons, makers of hats, caps and furs, when he received this letter from Swift Hurlburt & Co., hatters in New York City.

William James Coleman was born in February 1814, in Sackville, Nova Scotia. He married Hannah Jane Lockhart about 1840, in Halifax. They were the parents of at least 5 sons and 3 daughters. He died on 9 April 1896, in Halifax, at the age of 82, and was buried in Camp Hill Cemetery, Halifax.

1871 census Halifax Ward 1, District 196, W J Coleman, age 55, Weslyan Methodist, merchant, with H J Coleman, 53, E Coleman, 23, F J Coleman, 21, J P Coleman, 19, F R Coleman, 17, A E Coleman. 13

McAlpine’s Halifax City Directory, 1871-1872, COLEMAN, W J & SONS, hats, caps, and furs, commission and forwarding merchants, 129 Granville. with Coleman, Wm J., h 87 Spring Garden Rd, and Coleman, W J jun, of W. J. Coleman & Sons, 128 Granville, h 43 Queen

McAlpine’s Halifax City Directory, 1877-1878, Coleman & Co, hats, caps & furs, 143 Granville

1881 census Ward 2, Halifax City has William J. Coleman, 67, born in Nova Scotia, occupation Hatter & Furier, Methodist, with his wife Hannah J. Coleman, 64, and children Fannie J. Coleman, 27, Ida P. Coleman, 22

McAlpine’s Halifax City Directory, 1884-1885, Coleman, William J, hatter, 209 Spring Garden Rd

The 1891 census Ward 2b, Halifax City, has Wm Jas Coleman, 77, Methodist, occupation Hat Fur Dealer, Number of Employees 4, father's birthplace Ireland, mother's birthplace, England, with his wife, Anna Jane Coleman, 74

Doggett's New-York City directory, 1845, lists SWIFT & HURLBURT, hats and caps, 158 Water

Henry Wilson's New York City Directory, 1852-3, has SWIFT HURLBURT & Co. hats, 207 Pearl

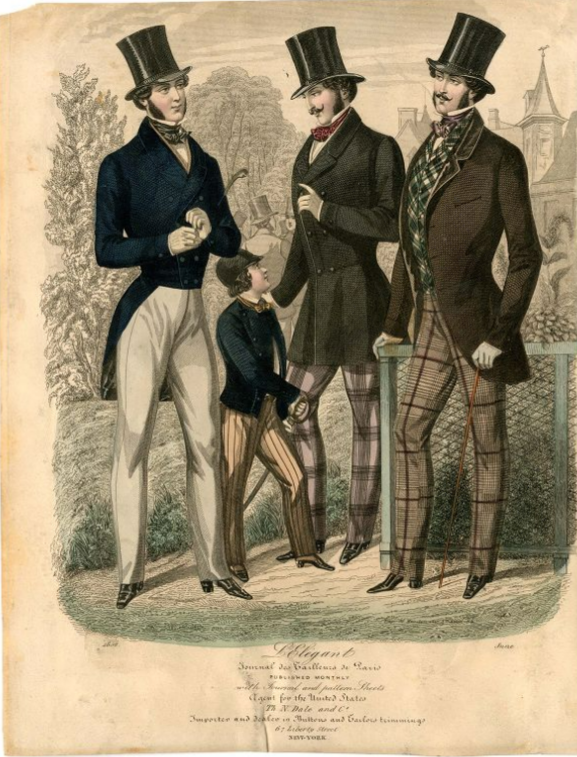

It is unlikely either W. J. Coleman & Sons or Swift Hurlburt & Co. were making women's bonnets. Those would have been made and sold by a milliner. Coleman's would have made men's top hats. The first historically verifiable top hat can be attributed to George Dunnage, a Middlesex hatter, who created the first top hat you and I would recognize in 1793.

At the time, top hats featured a very curved, hourglass shape, being narrower at the center of the cylinder than at the base and top. They are quickly adopted for their exquisite craftsmanship and the panache they give their wearers. They soon became the perfect gentleman's hat of choice and were adopted by all social classes in a form or another. They are made of beaver fur felt or silk for the wealthier, and of stiffened wool felt for the lower classes. During the 1850s, top hats reached new heights. This is the time when the stovepipe hat appeared, a top hat that could reach up to 20 cm high. It was French hatter Antoine Gibus who, around 1840, invented the chapeau claque, or opera hat. This collapsible top hat is mounted on a metal structure with springs that allows you to fold your hat, in order to store it easily under the seat, in the locker room or in your luggage. The popularity of the top hat reached its peak towards the end of the 19th century. It takes on more reasonable proportions, stabilizing around 12 cm to 15 cm in height. All gentlemen were expected to wear a top hat at formal and/or important events. For everyday wear, the bowler had been invented in England in 1849 and the style would have soon crossed the Atlantic to Halifax.

Erethism, or mercury poisoning, was an occupational hazard for hatters. Erethism is characterized by behavioral changes such as irritability, low self-confidence, depression, apathy, shyness and timidity, and in some extreme cases with prolonged exposure to mercury vapors, by delirium, personality changes and memory loss. People with erethism often have difficulty with social interactions. Associated physical problems may include a decrease in physical strength, headaches, general pain, tremors, and an irregular heartbeat. Historically, this was common among felt-hatmakers who had long-term exposure to vapors from the mercury they used to stabilize the wool in a process called felting, where hair was cut from a pelt of an animal such as a rabbit or beaver. The industrial workers were exposed to the mercury vapors, giving rise to the expression "mad as a hatter". Especially in the 19th century, inorganic mercury in the form of mercuric nitrate was commonly used in the production of felt for hats. During a process called carroting, in which furs from small animals such as rabbits, hares or beavers were separated from their skins and matted together, an orange-colored solution containing mercuric nitrate was used as a smoothing agent. The resulting felt was then repeatedly shaped into large cones, shrunk in boiling water and dried. In treated felts, a slow reaction released volatile free mercury. Hatters who came into contact with vapours from the impregnated felt often worked in confined areas. During the Victorian era the hatters' malaise became proverbial, as reflected in popular expressions like "mad as a hatter" and "the hatters' shakes".

The first description of symptoms of mercury poisoning among hatters appears to have been made in St Petersburg, Russia, in 1829. In the United States, a thorough occupational description of mercury poisoning among New Jersey hatters was published locally by Addison Freeman in 1860. Adolph Kussmaul's definitive clinical description of mercury poisoning published in 1861 contained only passing references to hatmakers, including a case originally reported in 1845 of a 15-year-old Parisian girl, the severity of whose tremors following two years of carroting prompted opium treatment. In Britain, the toxicologist Alfred Swaine Taylor reported the disease in a hatmaker in 1864.

In 1869, the French Academy of Medicine demonstrated the health hazards posed to hatmakers. Alternatives to mercury use in hatmaking became available by 1874. In the United States, a hydrochloride-based process was patented in 1888 to obviate the use of mercury, but was ignored.

Comments